The easy answer is really a semantic one: nothing that can be done in cyber (information technology) is directly comparable to widespread kinetic destruction of military forces.

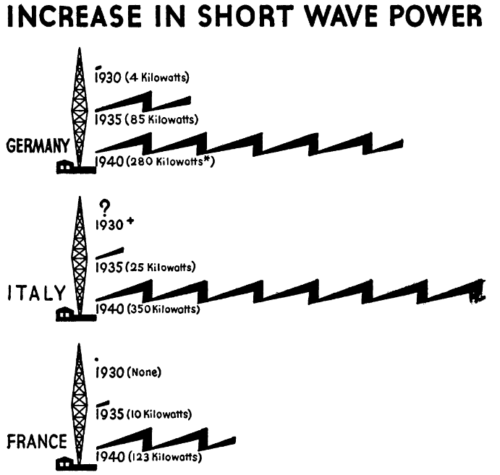

Once something approaches that level of destructive force, it’s no longer really the domain of cyber. In other words we don’t really call it a voice attack if someone speaks into a microphone instead of turning keys to launch nuclear weapons. As the 1941 book “War on the Short Wave” put it on page 69:

Gunpowder it it is said, was first used as a holiday crackers. Radio in the early days operated to give men pleasure. Both have been turned to use in wars and nations have used broadcasting as an ally of the bomb.

Ally of the bomb. Not the bomb.

More seriously, the problem lies in the psychological power of the narrative. Despite basic early indicators, the attack on Pearl Harbor came as a “bolt out of the blue” on a major military target.

Their duty done, George, who was new to the unit, took over the oscilloscope for a few minutes of time-killing practice. […] Their device could not tell its operators precisely how many planes the antenna was sensing, or if they were American or military or civilian. But the height of a spike gave a rough indication of the number of aircraft. And this spike did not suggest two or three, but an astonishing number—50 maybe, or even more. “It was the largest group I had ever seen on the oscilloscope,” said Joe.

It was just past 7 in the morning on December 7, 1941 when the US failed to recognize over 300 Japanese planes about to unleash massive devastation on the Navy.

Take now for example a modern nuclear weapon that delivers in less than half an hour a surprise attack using an intercontinental missile.

Such a surprise on the right targets might prevent any kind of counter-strike. That is an apt framing for lightning dropping out of a clear blue sky and zapping capabilities.

As I’ve documented here before, however, it’s been a VERY long road since at least the 1970s telling us that a normative situation of information technology is more like continuous grinding attacks everywhere all the time.

Andrew Freedman writes about this phenomenon as “more like a hill we’re sliding down at ever-increasing speed”.

We can choose to alter course at any time by hitting the brakes…. But the longer we wait, the faster we’ll be traveling, and the more effort it will take to slow down and achieve the cuts that are needed. And we’ve already waited a long time to start pumping the brakes.

Please note, this is NOT to be confused with a slippery slope, which implies there are no brakes and thus is a fallacy.

It’s pretty much the opposite of Pearl Harbor as a narrative — a never-ending thunderous grey downpour leading to increasing rate and scope of failures. There is no bolt from blue, no sudden wake-up event without warning.

Imagine Pearl Harbor being told to you as a story about constant rust forming on ships that also have a problem with petty theft and the occasional targeted adversary. Sound different? THAT is cyber.

Otherwise wouldn’t any event such as this one rise to became a Pearl Harbor?

Eighty percent of email accounts used in the four New York-based US Attorney offices were compromised [by Russian military intelligence].

We’d be talking about tens of thousands of Pearl Harbor events each year (when in reality who even remembers the Code Spaces cloud breach of 2014 instantly putting them out of business). Or let me put it this way: for nearly half the years since Pearl Harbor the US has talked about a Cyber Pearl Harbor.

If anything, 2016 was it and even that was more like a poorly done coup than a destructive bombing preventing counterattack.

My main quibble with my own argument here is the poor quality practices of companies like Uber and Tesla. Nobody needs to be sending intercontinental missiles to America when they can remotely automate widespread carjacking instead.

Take that kind of bad engineering and maliciously route 40,000 cars in an urban center and you’ve got a surprise mass casualty event via information technology vulnerabilities… which sounds an AWFUL lot like a bolt out of the blue when you look at tens of thousands of highly-explosive Teslas being adversarial dive-bombers loitering about stealthily just waiting to happen.

The counterargument to my counterargument is that Tesla has been killing a LOT of people, being less safe after installing fraudulent “autopilot”, and at least 3X more likely than comparable cars to kill its driver. We won’t see a Pearl Harbor even in driverless when Tesla is allowed to continue normalizing devastating crashes and ignore its mounting death tolls.

Anyway, all this debate about the relevance of Pearl Harbor has come up again in another article, which bizarrely claims a negative: that we didn’t see the lack of a cyber Pearl Harbor coming.

Over the past decade, cyber warfare has changed in ways the experts didn’t see coming.

Let me say that again. They’re suggesting we didn’t see a lack of Pearl Harbor attack, when that is exactly what we saw (those predicting a bolt of blue always faced opposition).

I mean their point is just flatly false.

As an expert (at least to some, hi mom!) in both cyber and military history I absolutely saw today’s situation coming and gave numerous very public talks and comments about it.

Hell, (to paraphrase military icons in movies) I even gave a presentation in 2012 dedicated to cyber warfare that predicted a lot of what mass media just started talking about now.

Meh.

The article goes on to say experts didn’t predict that laying networks into repressive regimes would increase repression, yet again that is false. Early reports said exactly that. It wasn’t rocket science.

You deliver into a power vacuum shiny new tools (let’s say a pitchfork, for example) and want to believe optimists that it won’t be used as a weapon or lead to oppression. Because why?

History and political science as a guide told us the opposite would come and that’s exactly what we’ve seen.