Usually I like to talk about making predictions about the future based on a reading of history.

However, I found two recent articles that forced me to think about more current publications helping to set a future course of science. Think Google, but not so evil because nothing to do with advertising.

First is a story about “Giant” that announced an index of 107 million papers in a way that cleverly navigates around present copyright laws.

Some researchers who have had early access to the index say it’s a major development in helping them to search the literature with software — a procedure known as text mining. Gitanjali Yadav, a computational biologist at the University of Cambridge, UK, who studies volatile organic compounds emitted by plants, says she aims to comb through Malamud’s index to produce analyses of the plant chemicals described in the world’s research papers. “There is no way for me — or anyone else — to experimentally analyse or measure the chemical fingerprint of each and every plant species on Earth. Much of the information we seek already exists, in published literature,” she says. But researchers are restricted by lack of access to many papers, Yadav adds. Malamud’s ‘General Index’, as he calls it, aims to address the problems faced by researchers such as Yadav.

Second is a paper on the prediction of research trends using computational analysis of available papers.

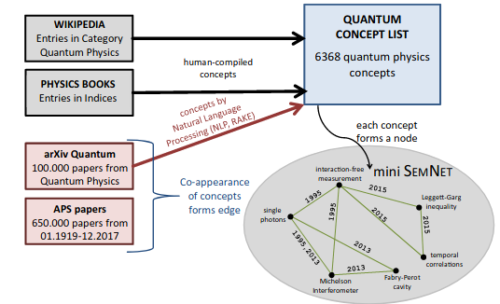

Here, we demonstrate the development of a semantic network for quantum physics, denoted SEMNET, using 750,000 scientific papers and knowledge from books and Wikipedia. We use it in conjunction with an artificial neural network for predicting future research trends. Individual scientists can use SEMNET for suggesting and inspiring personalized, out-of-the-box ideas. Computer-inspired scientific ideas will play a significant role in accelerating scientific progress, and we hope that our work directly contributes to that important goal.

It’s always tempting to invoke Douglas Adams’ famous “42” story when reading these types of articles.

The methods used look more mathematical, and rushed to conclusion, compared with something the seasoned historian might do to validate trends or meaning.