As I read current news from the press about America losing trust in news, I am reminded of the long history of this issue.

One of the more tragic stories is this one from 1837:

Elijah Lovejoy was a reverend and printer in Alton, Illinois, in the 1830s. He was the editor for the Alton Observer, a religious newspaper with a pro-abolition stance. His journey to Alton was not a smooth one. He had three printing presses destroyed before he settled in Alton—all three times the vandalism was in response to abolitionist editorials in his newspaper. On November 7th, 1837, a mob gathered outside of the warehouse that held his printing press. After exchanging gunfire with the crowd, Lovejoy was killed and his press was destroyed a fourth and final time. He was buried on November 9th, what would have been his 35th birthday.

Americans destroyed Lovejoy’s press four times in deadly “cancel culture” mobs, murdering him in the last attack.

Lovejoy had been forced to Move to Alton, Illinois after his paper in 1836 dared to publish a drawing and describe a lynching in St. Louis, Missouri. A white mob had chained a free black man to a stake and then threw stones at him as they burned him alive.

Leaders of the Missouri city objected to anyone reporting these events as fact. Lovejoy not only reported it in detail, also he asserted that while a man may deserve to die only savages would dance around their victim while the fire did the work. For this Lovejoy’s press was destroyed by the men he labeled savages, and he was forced out of Missouri.

Lovejoy had prepared himself with nearly 20 defenders in an Alton, Illinois building made of stone, just across the river from St. Louis. His new press was guarded with guns (as explicitly authorized by the Mayor), yet an angry white nationalist mob swarmed in to shoot him dead.

“Burn ’em out,” someone outside shouted. “Shoot every damned abolitionist as he leaves.” When men with torches climbed onto the roof, defenders of the press opened fire, killing one rioter and forcing others to retreat. In the eerie quiet, editor Elijah P. Lovejoy stepped outside for a look. Five shots [from attackers hiding in a wood pile nearby] riddled him. “Oh God, I am shot,” he said as he fell.

The press of liberty and freedom was so hated by the lawless mob it set about to destroy the heavy machinery by dumping it into a river instead of just printing something else.

The mob reportedly threw his press, which weighed nearly half a ton, into the river near the warehouse where the Ardent Mills flour mill is located today.

You might have gathered the police didn’t intervene. You might also have figured out also that nobody, not a single attacker, was held responsible. Officials in Illinois and even newspapers went mostly quiet.

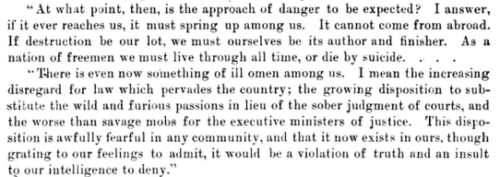

There was one very notable exception by a twenty-eight year old representative of the state who spoke out against lawlessness destroying freedom of speech — vigorously denouncing mobs that “throw printing presses into rivers, shoot editors”.

His name was Abraham Lincoln.

Twenty years later in 1857 Lincoln also would write in a private letter how significant this event was for American history.

Lovejoy’s tragic death for freedom in every sense marked his sad ending as the most important single event that ever happened in the new world.

Thus 1837 seems crucial to study and understand. The violent mob tactics in 1830s mirror behavior of extremist white nationalist groups today who attack modern liberty movements (e.g. BLM) and who try to undermine trust in the press.