When I visited Lyft HQ when it first opened, they had a large mural timeline of their origin story that went something like this:

In 2006 Logan Green went to Zimbabwe and observed a system of crowd-sourced carpool networks. He came back to America and made a copy he called Zimride (Zimbabwe Ride).

I’ll never forget being in the office (for meetings) and having staff relate this mural story to me, because they said their founder vacationed in Africa after college and marveled at the “safety” of private drivers; white parents having a method of ride-sharing their kids to school (called the “lift system” in South Africa).

The Lyft staff didn’t say the exact word apartheid, of course, because they were blandly relating Rhodesian transportation history as if it were like any other system. It was based on white families driving their children to elitist schools, but that’s not how they framed it.

Anyway this Lyft story telling of their “safe” transport system origins from Africa raised alarms for me, given context of Zimbabwean history.

I also noticed the company seems to tell a very different story to the press, claiming their founder was just an admirer of taxis.

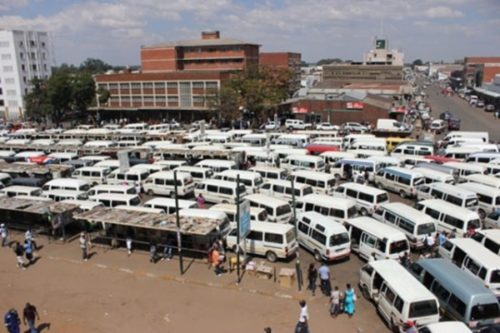

Zimride, in fact, is not a derivation of Zimmer’s name but a riff on Zimbabwe, where Green, now CEO, had observed the local propensity for ridesharing in minivan taxis.

This press brief makes no sense at all when you think about it even a little.

First, Lyft never attempted to work with taxis in America. From the start the company was billed as a whole alternative to taxis systems, so why would they say they liked African taxis?

More to the point who comes back from a vacation to an African country with the idea for a wealthy white person alternative to taxis in America? Does that really sound like observing Zimbabwean minivan taxis?

This kind of narrative disconnect between internal and external statements was highlighted in 2017 when Lyft eventually came around to launching a private “bus” service. I mean why didn’t they start with minivan taxis if that’s what they observed?

Anyway, eleven years late, their approach didn’t escape some predictable and obvious criticisms.

The Lyft Shuttle is pretty much a glorified city bus — with fewer poor people. The ride-sharing company’s much-hyped shuttle service seems designed to segregate transit customers by class.

A privilege bus.

Second, ride-sharing in minivan taxis (even pickups beds) has been a global phenomenon of efficient transport, not a concept unique to Zimbabwean culture. There must have been something unique to Zimbabwe being the origin story, aside from minivan taxis.

I’ve traveled all over the world in the minivan/microbus/kombi taxi and similar. From Poland to Indonesia, Zimbabwe to Philippines … you can find vehicles carrying 8-12 people running regular routes. When I was at EMC in 2012 I even worked with security systems to help make Pakistan’s “pink bus” safer (women only, with women guards riding and cameras) .

This is because a modern private micro bus naturally evolved by community-led transit planners to be an optimal solution on a development path towards achieving higher-volume buses or trains (a step on the way moving people further away from cars).

Lyft doesn’t fit that model, not at all. They started with cars where drivers were “safe” as if your friend or on your “side”, pandering openly to wealthy young white professionals and kids in school. That’s the apartheid white parents car-sharing story.

Again, a micro bus taxi service is not even close to what Lyft initially was planning, so the more likley Zimbabwean root is the Rhodesian/South African “lift system”.

After observing the micro bus taxis on predictable routes, CEO Green did the opposite and put passengers in the front seat of small cars on unrestricted paths. It sounds more like a trip to Zimbabwe left the founder thinking “how can I setup a service so white people like me can avoid crowded public transit such as the Zimbabwean taxi bus system”.

Anyway 2013 the founder decided to rename his original creation “Lyft”, the same as the apartheid “lift system” white parents used to shuttle their racist families and avoid the black taxis. The renaming meant a complete jettison of the Zimbabwe reference as the original name was sold to Enterprise.

The African root reference only lived on with that painted mural in the office, which I only happened to see because they invited me inside and told me a wild yet inconsistent story of appropriation. They’ve since moved their HQ and evidence of the mural is surely long gone.

You might be thinking the link to apartheid’s “lift system” is uncanny, yet insufficient on its own as just a coincidental name.

Let me now also poke here at the issue of a pink “carstache” wired to the front of original Lyft vehicles.

They were explained to me as highly distinguishable “safety” marketing for ride shares. It supposedly was meant to give riders obvious physical safety signaling. And yet anyone could buy one and celebrities promoted owning them.

A person who would dare to put a big pink thing on their car (remember the “pink bus” in 2012 Pakistan?) was advertised as someone who wouldn’t be physically dangerous to Lyft’s target population (white women).

…little-known fact: The bright pink color was inspired not only by the founders’ desire to seem friendly and bold, but also to make their branding a bit less masculine than competitors, and nod to their very welcome view toward female passengers and drivers, as well as emphasis on safety for women.

“Funny” big pink facial features when you meet your driver may instead read to some as two white guys’ doing some really insensitive appropriation of imagery in black culture. Look at the top lip in this iconic anti-black image:

And notice how even Uber tried to portray Lyft’s requirement that riders must fist-bump drivers.

What’s so weird about requiring Lyft riders to do a fist-bump?

…the pound is “a gesture of solidarity and comradeship… also used in a celebratory sense and sometimes as a nuanced greeting among intimates and/or those with a shared social history”. They trace that history in mainstream black culture to the Sixties, when African-American soldiers fighting in Vietnam used the dap… fists meet vertically, one above the other.

I wonder if Lyft had anyone black in executive management on board with the big pink mustache/lip and forced fist-bump concepts. I found their 2018 diversity report illuminating, given they were on a massive hiring spree doubling the size of the company and yet had 0% black staff in technical leadership.

Speaking of which, did you know a whopping “75% of white Americans have no friends of color at all.”

Even worse, as you might guess from a company started by a white college grad unwittingly claiming inspiration from apartheid who partnered with a Wall Street banker, Lyft has been widely implicated in systemic victimization of women.

A single SF driver repeatedly attacked women over five years before police managed to track him down. That’s just one of literally thousands of their unsafe ride-share cases highlighted by 20 women suing the company.

“Lyft has been aware of the staggering number of assaults and rapes that occur in their vehicles for years. They continue to conceal those numbers from the public and Lyft customers,” Bomberger said in a statement. “That is not a commitment to safety. It is a commitment to profits.”

Obviously Lyft has totally obliterated their origin story now. You won’t find them speaking of Africa or the white woman “safety” angle in the same way. They now downplay the big pink face features, quit the fist-bump, and strut about like ride-sharing was just something they invented while bored and traveling around California.

It may be important to revisit the whole origin story again, however, as researchers have been looking more deeply at the decision algorithms and continue to reveal racism in ride-sharing platforms.

…fares tended to be higher for drop-offs in Chicago neighborhoods with high non-white populations…an earlier report published in October 2016 by the National Bureau of Economic Research that found in the cities of Boston and Seattle male riders with African American names were 3 times more likely to have rides canceled and wait as much as 35% longer for rides.