More and more often I see those experienced in technology very awkwardly address issues of political science.

- A malware reverser will speculate on terrorist motives.

- An expert with network traffic analysis will make guesses about organized crime operations.

When a journalist asks an expert in information security to explain the human science of an attack, such as cultural groups and influences involved, answers appear more like quips and jabs instead of deep thought from established human science or study.

This is unfortunate since I suspect a little reading or discussion would improve the situation dramatically.

My impression is there is no clear guide floating around, however. When I raise this issue I’ve been asked to put something together. So, given I spent my undergraduate and graduate degrees in the abyss of political philosophy (ethics of humanitarian intervention, “what kind of job will you do with that”), perhaps I can help here in the ways that I was taught.

Reading “The Three-Body Problem” would help, perhaps, but Chinese Sci-Fi seems too vague a place to start from…

Set against the backdrop of China’s Cultural Revolution, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. Meanwhile, on Earth, different camps start forming, planning to either welcome the superior beings and help them take over a world seen as corrupt, or to fight against the invasion.

I offer Chinese literature here mainly since many attempts to explain “American” hacker culture tend to start with Snowcrash or similar text.

Instead of that, I will attempt to give a far more clear example, which recently fell on my desk.

Say Silent Chollima One More Time

About two years ago a private company created by a wealthy businessman came out of stealth mode. It was launched with strong ties to the US government and ambitious goals to influence the world of information security investigations.

When 2013 kicked off CrowdStrike was barely known outside of inner-sanctum security circles. The stealth startup–founded by former Foundstone CEO, McAfee CTO, and co-author of the vaunted Hacking Exposed books George Kurtz–was essentially unveiled to the world at large at the RSA Security Conference in February.

Today in 2015 (2 years after the company was announced and 4 years after initial funding) take note of how they market the length of their projects/experience; they slyly claim work dating way back in 2006, at least 4 years before they existed.

Interviewer: What do you make of the FBI finding — and the president referred to it — that North Korea and North Korea alone was behind this attack?

CrowdStrike: At CrowdStrike, we absolutely agree with that. We have actually been tracking this actor. We actually call them Silent Chollima. That’s our name for this group based that is out of North Korea.

Interviewer: Say the name again.

Crowdstrike: Silent Chollima. Chollima is actually a national animal of North Korea. It’s a mythical flying horse. And we have been tracking this group since 2006.

Hold on to that “mythical flying horse” for a second. We need to talk about 2006.

CrowdStrike may have internally blended their own identity so much with the US government they do not realize those of us outside their gravy train business concept cringe when lines are blurred between a CrowdStrike marketing launch and government bureaus. I think hiring many people away from the US government still does not excuse such casual use of “we” when speaking about intelligence from before the 2013 company launch date.

Remember the mythical flying horse?

Ok, good, because word use and definitions matter greatly to political scientists. Reference to a mythological flying horse is a different kind of sly marketing. CrowdStrike adds heavy emphasis to their suspects and a leading characterization where none is required and probably shouldn’t be used. They want everyone to take note of what “we actually call” suspects without any sense of irony for this being propagandist.

Some of their “slyness” may be just examples in sloppy work, insensitive or silly labeling for convenience, rather than outright attempts designed to bias and change minds. Let’s look at their “meet the adversaries” page.

Again it looks like a tossup between sloppy work and intentional framing.

Look closely at the list. Anyone else find it strange that a country of Tiger is an India?

What kind of mythical animal is an India? Ok, but seriously, only the Chollima gets defined by CrowdStrike? I have to look up an India?

We can surmise that Iran (Persia) is being mocked as a Kitten while India gets labeled with a Tiger (perhaps a nod to Sambo) as some light-hearted back-slapping comedy by white men in America to lighten up the mood in CrowdStrike offices.

Long nights poring over forensic material, might as well start filing with pejorative names for foreign indicators because, duh, adversaries.

Political scientists say the words used to describe a suspect before a court trial heavily influence everyone’s views. An election also has this effect on deciding votes. Pakistan has some very interesting long-term studies of voting results from ballots for the illiterate, where candidates are assigned an icon.

Imagine a ballot for voting, and you are asked to choose between a poisonous snake or a fluffy kitten. This is a very real world example.

Social psychologists have a test they call Implicit Association that is used in numerous studies to measure response time (in milliseconds) of human subjects asked to pair word concepts. Depending on their background, people more quickly associate words like “kitten” with pleasant concepts, and “tiger” more quickly with unpleasant ideas. CrowdStrike above is literally creating the associations.

As an amusing aside it was an unfortunate tone-deaf marketing decision by top executives (mostly British) at EMC to name their flag-ship storage solution “Viper”. Nobody in India wanted to install a Viper in their data-centers, hopefully for obvious reasons.

Moreover, CrowdStrike makes no bones about saying someone they suspect is considered guilty until proven innocent. This unsavory political philosophy comes through clearly in another interview (where they also take a moment to throw Chollima into the dialogue):

We haven’t seen the skeptics produce any evidence that it wasn’t North Korea, because there is pretty good technical attribution here. […] North Korea is one of the few countries that doesn’t have a real animal as a national animal. […] Which, I think, tells you a lot about the country itself.

Let me highlight three statements here.

- We haven’t seen the skeptics produce any evidence that it wasn’t North Korea

- North Korea is one of the few countries that doesn’t have a real animal as a national animal.

- Which, I think, tells you a lot about the country itself.

We’re going to dive right into those.

I’ll leave the “pretty good technical attribution” statement alone here because I want to deal with that in a separate post.

Let’s break the remaining three sentences into two separate parts.

First: Skeptics Haven’t Produced Evidence

Is it a challenge for skeptics to produce counter-evidence? Bertrand Russell eloquently and completely destroyed such reasoning long ago. His simple celestial teapot analogy speaks for itself.

If I were to suggest that between the Earth and Mars there is a china teapot revolving about the sun in an elliptical orbit, nobody would be able to disprove my assertion provided I were careful to add that the teapot is too small to be revealed even by our most powerful telescopes. But if I were to go on to say that, since my assertion cannot be disproved, it is intolerable presumption on the part of human reason to doubt it, I should rightly be thought to be talking nonsense.

This is the danger of ignoring lessons from basic political science, let alone its deeper philosophical underpinnings; you end up an information security “thought leader” talking absolute nonsense.

CrowdStrike may as well tell skeptics to produce evidence attacks aren’t from a flying horse.

The burden of proof logically and obviously remains with those who sit upon an unfalsifiable belief. As long as investigators offer statements like “we see evidence and you can’t” or “if only you could see what we see” then the burden can not easily and so negligently shift away.

Perhaps I also should bring in the proper, and sadly ironic, context to those who dismiss or silence the virtue of skepticism.

Studies of North Korean politics emphasize their leaders often justify total control while denying information to the public, silencing dissent and making skepticism punishable. In an RT documentary, for example, North Korean officers happily say they must do as they are told and they would not question authority because they have only a poor and partial view; they say only their dear leader can see all the evidence.

Skepticism should not be rebuked by investigators if they desire, as scientists tend to, for challenges to help them find truth. Perhaps it is fair to say CrowdStrike takes the very opposite approach of what we often call crowd source?

Analysts within the crowd who speak out as skeptics tend to be most practiced in the art of accurate thought, precisely because caution and doubt are not dismissed. Incompleteness is embraced and examined. This is explained with recent studies. Read, for example, a new study called “Psychology of Intelligence Analysis: Drivers of Prediction Accuracy in World Politics” that highlights how and why politics alter analyst conclusions.

Analysts also operate under bureaucratic-political pressure and are tempted to respond to previous mistakes by shifting their response thresholds. They are likelier to say “signal” when recently accused of underconnecting the dots (i.e., 9/11) and to say “noise” when recently accused of overconnecting the dots (i.e., weapons of mass destruction in Iraq). Tetlock and Mellers (2011) describe this process as accountability ping-pong.

Then consider an earlier study regarding what makes people into and “superforecasters” when they are accountable to a non-political measurement.

…accountability encourages careful thinking and reduces self-serving cognitive biases. Journalists, media dons and other pundits do not face such pressures. Today’s newsprint is, famously, tomorrow’s fish-and-chip wrapping, which means that columnists—despite their big audiences—are rarely grilled about their predictions after the fact. Indeed, Dr Tetlock found that the more famous his pundits were, the worse they did.

CrowdStrike is as famous as any company can get, as designed from flashy launch. Do they have any non-political, measured accountability to go with their pomp and circumstance?

Along with being skeptical, analysts sometimes are faulted for being grouchy. It turns out in other studies that people in bad moods remember more detail in investigations and provide more accurate facts, because they are skeptical. The next time you want to tell an analyst to brighten up, think about the harm to the quality of their work.

Be skeptical if you want to find the right answers in complex problems. And stay grouchy if you want to be more detail oriented.

Second: A Country Without a Real Animal

Going back to the interview statement by CrowdStrike, “one of the few countries” without “a real animal as a national animal” is factually easy to confirm. It seems most obviously false.

With a touch of my finger I find mythical national animals used in England, Wales, Scotland, Bhutan, China, Greece, Hungary, Indonesia, Iran, Portugal, Russia, Turkey, Vietnam…and the list goes on.

Don’t forget the Allies’ Chindits in WWII, for example. Their name came from corruption of the Burmese mythical chinthe, a lion-like creature (to symbolize a father lion slain by his half-lion son who wanted to please his human mother) that frequently guards Buddhist temples in pairs of statutes.

Even if I try to put myself in the shoes of someone making such a claim I find it impossible to see how use of national mythology could seem distinctly North Korean to anyone from anywhere else. It almost makes me laugh when I think this is a North Korean argument for false pride: “only we have a mythological national animal”.

The reverse also is awkward. Does anyone really vouch for a lack of any real national animal for this territory? In the mythical eight years of CrowdStrike surveillance (arguably two years) did anyone notice, for example, that Plestiodon coreensis stamps were issued (honoring a very real national lizard unique to North Korea) or the North Korean animation shows starring the very real Sciurus vulgaris and Martes zibellina (Squirrel and Hedgehog)?

From there, right off the top of my head, I think of national mythology frequently used in Russia (two-headed monster) and England (monster being killed):

And then what about America using mythical beasts at all levels, from local to national. Like what does it say when a Houston “Astro” play against a Colorado “Rocky”? Are we really supposed to cheer for a mythical mountain beast, some kind of anthropomorphic purple triceratops, or is it better that Americans rally around a green space alien with antennae?

Come on CrowdStrike, where did you learn analysis?

At this point I am unsure whether to go on to the second half of the CrowdStrke statement. Someone who says national mythical animals are unique to North Korea is in no position to assert it “tells you a lot about the country itself”.

Putting myself again in their shoes, CrowdStrike may think they convey “fools in North Korea have false aspirations; people there should be more skeptical”.

Unfortunately the false uniqueness claim makes it hard to unravel who the fools really are. A little skepticism would have helped CrowdStrike realize mythology is universal, even at the national level. So what do we really learn when a nation has evidence of mythology?

In my 2012 Big Data Security presentations I touched on this briefly. I spoke to risks of over-confidence and belief in data that may undermine further analytic integrity. My example was the Griffin, a mythological animal (used by the Republic of Genoa, not to mention Greece and England).

Recent work by an archeologist suggests these legendary monsters were a creative interpretation by Gobi nomads of Protocerotops bones. Found during gold prospecting the unfamiliar bones turned into stories told to those they traded with, which spread further until many people were using Griffins in their architecture and crests.

Ok, so really mythology tells us that people everywhere are creative and imaginative with minds open to possibilities. People are dreamers and have aspirations. People stretch the truth and often make mistakes. The question is whether at some point a legend becomes hard or impossible to disprove.

A flying horse could symbolize North Koreans are fooled by shadows, or believe in legends, but who among us is not guilty of creativity to some degree? Creativity is the balance to skepticism and helps open the mind to possibilities not yet known or seen. It is not unique to any state but rather essential to the human pursuit of truth.

Be creative if you want to find the right answers in complex problems.

Third: Power Tools and Being More Informed Versus Better Informed

Intelligence and expertise in security, as you can see, does not automatically transfer to a foundation for sound political scientific thought. Scientists often barb each other about who has more difficult challenges to overcome, yet there are real challenges in everything.

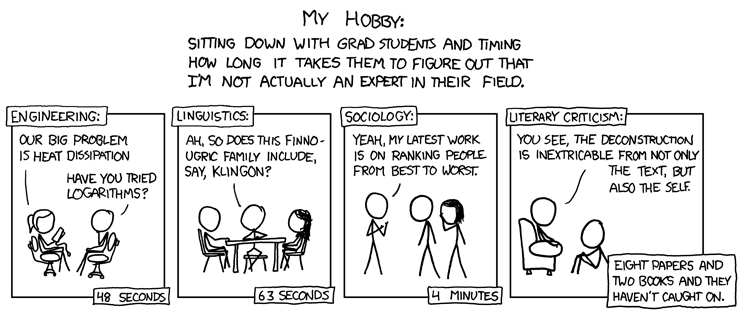

I think it important to emphasize here that understanding human behavior is very different skill. Not a lessor skill, a different one. XKCD illustrates how a false or reverse-confidence test is often administered:

Being the best brain surgeon does not automatically make someone an expert in writing laws any more than a political scientist would be an expert at cutting into your skull.

Basic skills in everything can be used to test for fraud (imposter exams) while the patience in more nebulous and open advanced thinking in every field can be abused. Multiplication tables for math need not be memorized because you can look them up to find true/false. So too with facts in political science, as I illustrated with mythology and symbolism for states. Quick, what’s your state animal?

Perhaps it is best said there are two modes to everything: things that are trivial and things that are not yet understood. The latter is what people mean when they say they have found something “sophisticated”.

There really are many good reasons for technical experts to quickly bone up on the long and detailed history of human science. Not least of them is to cut down propaganda and shadows, move beyond the flying horses, and uncover the best answers.

The examples I used above are very specific to current events in order to clarify what a problem looks like. Hopefully you see a problem to be solved and now are wondering how to avoid a similar mistake. If so, now I will try to briefly suggest ways to approach questions of political science: be skeptical, be creative. Some might say leave it to the professionals, the counter-intelligence experts. I say never stop trying. Do what you love and keep doing it.

Achieving a baseline to parse how power is handled should be an immediate measurable goal. Can you take an environment, parse who the actors are, what groups they affiliate with and their relationships? Perhaps you see already the convenient parallels to role based access or key distribution projects.

Aside from just being a well-rounded thinker, learning political science means developing powerful analytic tools that quickly and accurately capture and explain how power works.

Stateful Inspection (Pun Intended)

Power is the essence of political thought. The science of politics deals with understanding systems of governing, regulating power, of groups. Political thinking is everywhere, and has been forever, from the smallest group to the largest. Many different forms are possible. Both the framework of the organization and leadership can vary greatly.

Some teach mainly about relationships between states, because states historically have been a foundation to generation of power. This is problematic as old concepts grow older, especially in IT, given that no single agreed-upon definition of “state” yet exists.

Could users of a service ever be considered a state? Google might be the most vociferously and openly opposed to our old definitions of state. While some corporations engage with states and believe in collaboration with public services, Google appears to define state as an irrelevant localized tax hindering their global ambitions.

A major setback to this definition came when an intruder was detected moving about Google’s state-less global flat network to perpetrate IP theft. Google believed China was to blame and went to the US government for services; only too late the heads of Google realized state-level protection without a state affiliation could prove impossible. Here is a perfect example of Google engineering anti-state theory full of dangerous presumptions that court security disaster

A state is arguably made up of people, who govern through representation of their wants and needs. Google sees benefits in taking all the power and owing nothing in return, doing as they please because they know best. An engineer that studied political science might quickly realize that removing ability for people to represent themselves as a state, forced to bend at the whim of a corporation, would be a reversal in fortune rather than progress.

It is thus very exciting to think how today technology can impact definitions for group membership and the boundaries of power. Take a look at an old dichotomy between nomadic and pastoral groups. Some travel often, others stay put. Now we look around and see basic technology concepts like remote management and virtual environments forcing a rethink of who belongs to what and where they really are at any moment in time.

Perhaps you remember how Amazon wanted to provide cloud services to the US government under ITAR requirements?

Amazon Web Services’ GovCloud puts federal data behind remote lock and key

The question of maintaining “state” information was raised because ITAR protects US secrets by requiring only citizens have access. Rather than fix the inability for their cloud to provide security at the required level, a dedicated private datacenter was created where only US citizens had keys. Physical separation. A more forward-thinking solution would have been to develop encryption and identity management solutions that avoided breaking up the cloud, while still complying with requirements.

This problem came up again in reverse when Microsoft was told by the US government to hand over data in Ireland. Had Microsoft built a private-key solution, linked to the national identity of users, they could have demonstrated an actual lack of access to that data. Instead you find Microsoft boasting to the public that state boundaries have been erased, your data moves with you wherever you go, while telling the US government that data in Ireland can’t be accessed.

Being stateful is not just a firewall concern, it really has roots in political science.

How Political is Clownstrike? An Ethics Test McAfee Ex-Execs Likely Can’t Pass

Does the idea of someone moving freely scare you more or a person who digs in for the long haul and claims proof of boundary violations where you see none?

Whereas territory used to be an essential characteristic of a state, today we wonder what membership and presence means when someone can remain always connected, not to mention their ability to roam within overlapping groups. Boundaries may form around nomads who carry their farms with them (i.e. playing FarmVille) and of course pastoralism changes when it moves freely without losing control (i.e. remote management of a Data Center).

Technology is fundamentally altering the things we used to rely upon to manage power. On the one hand this is of course a good thing. Survivability is an aim of security, reducing the impact of disaster by making our data more easily spread around and preserved. On the other hand this great benefit also poses a challenge to security. Confidentiality is another aim of security, controlling the spread of data and limiting preservation to reduce exposure. If I can move 31TB/hr (recent estimate) to protect data from being destroyed it also becomes harder to stop giant ex-filtration of data.

From an information security professional’s view the two sides tend to be played out in different types of power and groups. We rarely, if ever, see a backup expert in the same room as a web application security expert. Yet really it’s a sort of complicated balance that rests on top of trust and relationships, the sort of thing political scientists love to study.

With that in mind, notice how Listverse plays to popular fears with a top ten “Ominous State-Sponsored Hacker Group” article. See if you now, thinking about a balance of power between groups, can find flaws in their representation of security threats.

It is a great study. Here are a few questions that may help:

- Why would someone use “ominous” to qualify “state-sponsored” unless there also exist non-ominous state-sponsored hacker groups?

- Are there ominous hacker groups that lack state support? If so, could they out-compete state-sponsored ones? Why or why not? Could there be multiple-affiliations, such that hackers could be sponsored across states or switch states without detection?

- What is the political relationship, the power balance, between those with a target surface that gives them power (potentially running insecure systems) and those who can more efficiently generate power to point out flaws?

- How do our own political views affect our definitions and what we study?

I would love to keep going yet I fear this would strain too far the TL;DR intent of the post. Hopefully I have helped introduce someone, anyone (hi mom!), to the increasing need for combined practice in political science and information security. This is a massive topic and perhaps if there is interest I will build a more formal presentation with greater detail and examples.

Updated 19 January: added “The Psychology of Intelligence Analysis” citation and excerpt.